African-American eating disorder survivor shares her message that eating disorders don't just affect 'thin, young, white affluent women'

Giva Wilkerson is an African-American woman and one of the nearly 30 million Americans who suffer from an eating disorder.

“I remember laying in bed and the hunger pains were so intense that I began to cry and I said to myself, ‘All you have to do is go downstairs and get something to eat,’” Wilkerson recalled of her 15-year struggle with anorexia. “And I wouldn't do it. And I was crying because I was hungry too because I was afraid to eat.”

Once Wilkerson, 36, began her recovery four years ago, she made it her mission to shatter the “huge” misconception that eating disorders only affect “thin, young, white affluent women.”

Wilkerson, of Philadelphia, is now the program manager at Project HEAL, a Colorado-based organization founded in 2008 that provides support for people with eating disorders. The organization also works to raise funds for those suffering who cannot afford treatment.

“You have people of all genders, all races, all classes, all cultures coming together to talk about this illness that has affected their lives,” Wilkerson said in an interview with "Good Morning America's" Ginger Zee, who has also been public about her struggle with anorexia.

Environmental stress (like racism and poverty) may make women of color more vulnerable to eating disorders. People of color though are less likely to receive help for their eating issues according to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA).

In one study where clinicians reviewed case studies demonstrating disordered eating symptoms, 44 percent identified the white woman’s eating behavior as problematic but only 17 percent identified the black woman’s eating behavior as problematic.

(MORE: 6 health screening tests millennials should know about)

In addition to women from all backgrounds and ages suffering from eating disorders, men do too.

Approximately one-in-three people struggling with an eating disorder is male and approximately 10 million males in the U.S. are affected at some point in their lives, according to the nonprofit NEDA.

Major League Baseball player Mike Marjama opened up last year about suffering from an eating disorder in high school and getting help through a five-day stay in an in-patient program.

"If I can maybe affect one person that doesn’t have to have their hopes and dreams taken away from them because they’re suffering from an eating disorder, and they’re able to follow their hopes and dreams, that’s all I really want," Marjama told "GMA" at the time about why he chose to speak out.

Eating disorders have no known cause but researchers are finding they are caused by a "complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors," according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Why people don't get help

As many as 70 percent of people who may have an eating disorder do not get treatment, according to Dr. Janet Taylor, a Florida-based psychiatrist.

Feelings of shame and not having access to adequate medical care can affect people’s ability to get treatment, Taylor explained. A focus on weight by medical professionals and not on patterns of eating can also delay treatment, according to Taylor.

Eating disorders must also be treated from both a mental health and medical health perspective, which can lead to a complicated patchwork of insurance coverage to wade through.

“It's so expensive and it's so hard to get,” Wilkerson said of treatment for eating disorders. “And honestly, it's important for you not only have access treatment but access to treatment that's close by.”

Eating disorders also take on different signs and symptoms in each person. The most common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

The results of not getting treatment can be deadly, statistics show. Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, according to data compiled by the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD), a non-profit organization.

How to get help

A chance to help someone suffering in silence from an eating disorder is exactly the reason Wilkerson is sharing her story.

"Who would have thought that just me, regular old me, could now be someone that people can identify with, that people want to talk to about this, who could potentially help someone," she said.

Symptoms of anorexia include everything from extremely restricted eating and extreme thinness to an intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted body image.

Over time, symptoms may also include physical changes like brittle hair and nails and dry and yellowish skin and potentially deadly complications like brain and heart damage, according to the NIMH.

People with bulimia nervosa may have symptoms like swollen salivary glands, a chronically inflamed and sore throat, severe hydration and acid reflux disorder, the NIMH reports.

Symptoms for binge-eating disorder can include eating fast during binge episodes, eating until a person is uncomfortably full and eating alone or in secret.

Recovery from an eating disorder requires a team approach that includes the support of everyone from family and friends to mental health professionals and medical doctors.

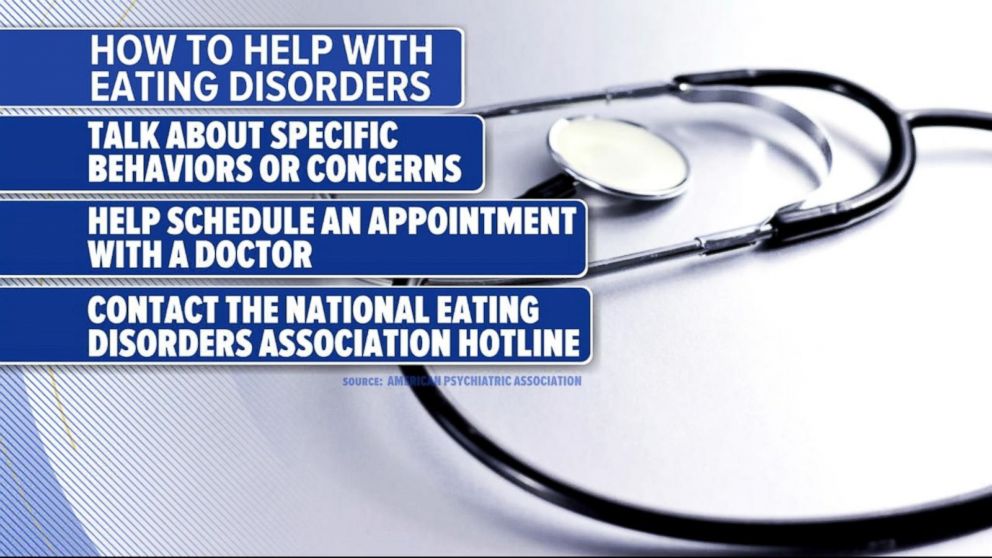

If you want to help someone who may have an eating disorder, these four steps are recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

1. Be empathic, but clear.

2. List signs or behaviors you have noticed and are concerned about.

3. Help locate a treatment provider and offer to go with your friend or relative to an evaluation.

4. Be prepared that the affected individual may be uncertain about seeking treatment.

For more information on eating disorders, including warning signs and how to find support and help, visit the National Eating Disorders Association.