Student debt crisis: This 28-year-old mom is 'drowning' in $80,000 of debt

Khallilah Beecham-Watkins and her family celebrated when she became the first person in her family to graduate from college.

She did so from her dream school, the University of Missouri.

Today, seven years after graduating, Beecham-Watkins, 28, of Chicago, is $80,000 in debt.

"I feel like I'm drowning," she told "Good Morning America." "When I graduated from undergrad, my student loan debt was $49,000."

"For me," she added, "being first-generation was expensive. My mom had the conversation with me of her hopes for me to go away to school, but we just weren't financially literate in terms of the cost."

"You sign a [loan] promissory note and you're like, 'OK, I kind of get it. I think I know what's going on,'" Beecham-Watkins said. "There's this dream that you get your education and you're going to get a good job and you won’t have to struggle to pay your student loans back because your degree is like your ticket to the American dream."

Beecham-Watkins, now married with a 1-year-old daughter, said scholarships helped cover some of her out-of-state tuition to Missouri, where she also worked part-time jobs during her undergrad years.

She and her husband, who also has student-loan debt, attended graduate school together in Washington, D.C., but left after one year because of the cost.

"It's six figures worth of debt," said Beecham-Watkins, who now works to help students avoid college debt as an education program specialist for a nonprofit. "I feel like it's my responsibility to yell through a megaphone that I don’t want [students] drowning in debt like I am."

Beecham-Watkins, who also runs her own social media company for extra income, estimates she will pay off her college debt by the age of 50.

"GMA" is spotlighting the stories of first-generation college students. Explore our full coverage.

The student-debt crisis

America's total student-loan debt is now around $1.5 trillion.

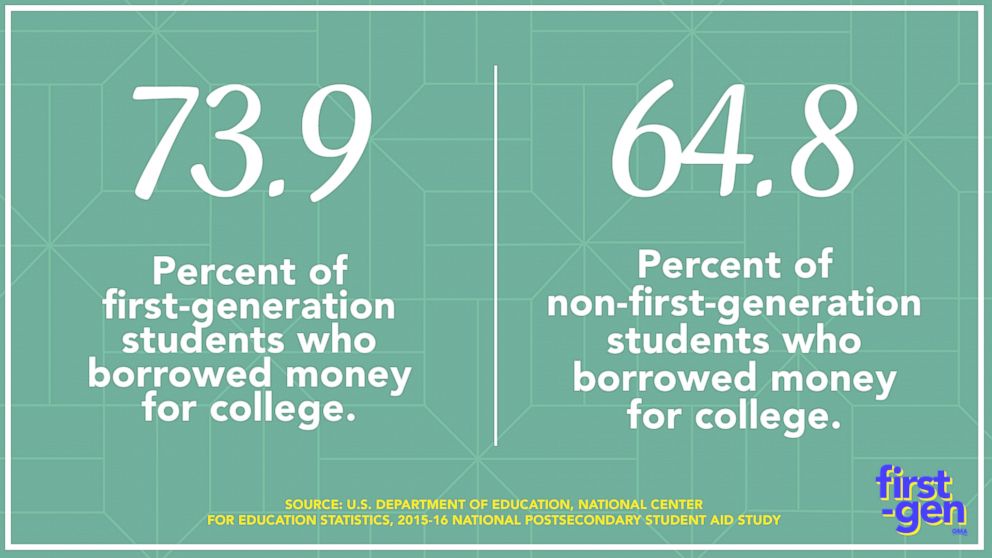

Nearly 74 percent of first-generation students in the class of 2015-16 borrowed money for their undergraduate education, according to the U.S. Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

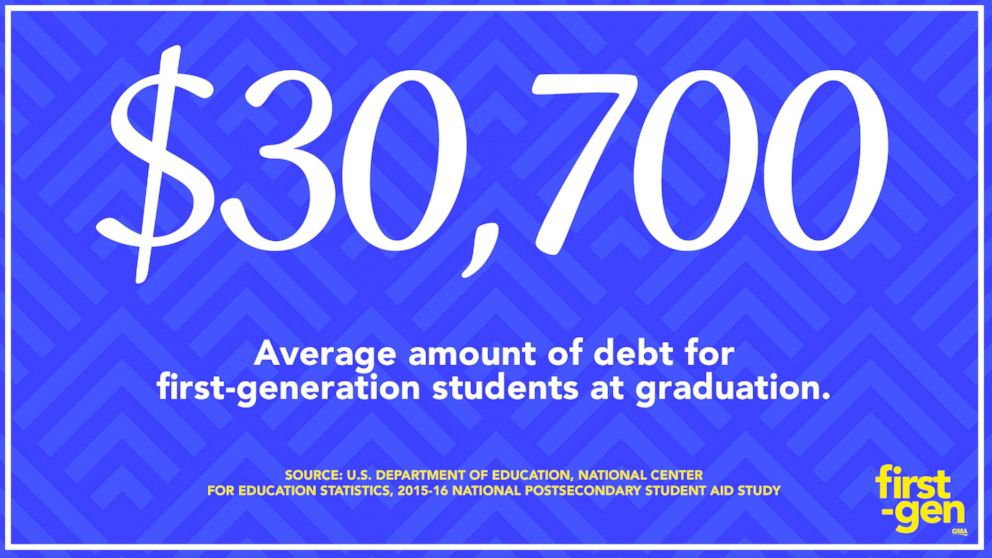

For first-generation students – students whose parents do not have a Bachelor’s degree or higher -- the average debt was nearly $30,700.

For non-first generation students in the class of 2015-16, the average debt was just over $28,000, with nearly 65 percent of non-first-generation students having borrowed money, according to NCES data.

The average debt for both first-generation and non-first-generation college students has followed a similar trajectory, increasing by around $6,500 over a span of eight years.

The difference? The weight of debt is more likely to turn first-generation students away from completing or even beginning their college degrees, experts say.

Debt dilemma for first-generation students

Beecham-Watkins' story is just one example of the dilemma faced by many first-generation college students when they try to achieve what no one in their family has.

First-generation students, about one-third of all U.S. college students, often do not have parental help when filling out financial forms, do not have a safety net of family wealth to fall back on and may be exempt from federal loans or financial aid if they are undocumented.

"When I went [to college], my parents knew nothing about FAFSA [Free Application for Federal Student Aid] or financial aid programs or how to pay for it," said Natalia Abrams, whose father did not attend college and whose mother attended college later in life. "There’s a real lack of knowledge when you're first-generation because you're figuring that out all on your own."

Abrams, a UCLA graduate, started a non-profit advocacy group, Student Debt Crisis, to try to change the way higher education is paid for in the U.S. She said her group, which also offers seminars and a helpline for students, noticed that first-generation students in particular fall into trouble because they dropped out of school because they carried too much debt to complete their degrees.

"Around 54 percent of first-gen students don’t complete their degree, and we know when students fail to complete [their degree], they tend to be one of the default members," she said. "It's just that vicious cycle where then they can fall into default, have their own financial struggles and it just creates lack of generational wealth that leads to it happening over and over again."

Small loans can turn into large loans for students over time as penalties and interests accumulate. Going into default on a student loan can lead to life-altering consequences ranging from garnished wages to damaged credit scores that impact one's ability to buy a home or additional financial aid. Some debtors are taken to court.

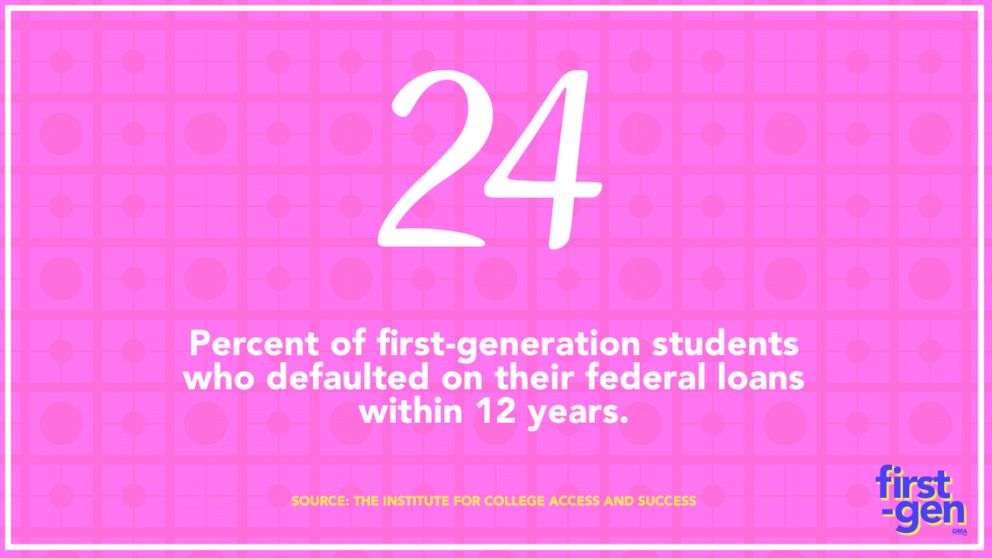

Nearly a quarter of first-generation students defaulted on their federal loans within 12 years, while only 14 percent of non-first-generation students defaulted during that time, according to the Institute for College Access and Success , an independent nonprofit organization.

Students most vulnerable to debt, including first-generation students, who completed their college degree were less than half as likely to have defaulted within 12 years than those who dropped out, the Institute found.

Abrams recalled one conversation with a first-generation student at a university in Tennessee who was $100,000 in debt her senior year. She questioned whether she should take on an additional $30,000 in debt to get her degree, or stop school and start working to pay off her loans.

"I told her, and I say this to all first-gen students, 'Finish your degree,'" Abrams said. "You still are better off having a degree, even with debt. That tide hasn’t changed yet. Studies are still showing you’ll make more over the course of your lifetime with a college degree."

When first-generation students stay in school, they graduate with economic mobility, data shows.

First-generation graduates from the University of California -- where first-generation students make up 42 percent of undergraduates -- surpass the median income of California residents with just a high school degree two years after graduation. Six years after graduation, they surpass their parents' households in median income.

Factors that lead to debt for first-gen students

Finishing a college degree remains a more difficult task for first-generation students compared to peers whose parents graduated from college.

First-generation, low-income students had a six-year bachelor's degree completion rate of 21 percent. Students who are first-generation but not low-income still had a bachelor’s degree completion rate of just 31 percent, according to data analyzed by the Pell Institute.

One factor making it harder for first-generation undergrads to finish their degree is the work they take on to lessen their debt.

"If you're first generation, you're more likely to take on a job either part time or full time," said Stefanie O'Connell, a millennial money expert and author of "The Broke and Beautiful Life."

"The big implication of that is if you're only able to devote half the time or less than your peers to your studies, it's more likely that you have trouble keeping up with the coursework and more likely that you might have trouble graduating," she explained.

First-generation students who do stay in school may take longer than four years to graduate, potentially adding tens of thousands dollars in debt. They also may miss out -- due largely to work and family obligations -- on the type of networking opportunities that could help them after they get their degree.

"It's not just the financial cost, it's the time cost," O'Connell said. "It's time you're not devoting to not just your studies but your social life, your connections. When you think about the opportunities that await you post [graduation], so much of that is who you know."

Some first-generation students are also taking out loans to pay not only for themselves at school but also for their families back home.

"I work with students on saving their refund money and not sending it home to their families," said Ja'Net Adams, a first-generation graduate who now runs a company that provides financial advice for students. "It’s giving them the courage to say, ‘No,’ because if not, you’re going to drop out with more student loan debt and you and your family are going to be in a worse situation."

Lack of financial education and coming from a low-income background can leave first-generation students more vulnerable to debt-relief scams, experts say. New rules recently proposed by the Trump administration would make it harder for students, first-generation included, who are defrauded by their schools to get their federal loans erased, according to The Associated Press.

First-generation students also more likely, if they are financially able, to take on private student loans, which often come with higher interest rates and fewer benefits.

The threat of debt on top of family financial strains may lead first-gen students to choose majors they are not passionate about.

"Some may feel obligated to pursue majors that they believe will lead to lucrative careers, without fully being invested in that major or career path," said Kevin Huie, director of Student Success Initiatives at the University of California, Irvine. "This can often affect students doing well academically if they are less motivated or interested in the classes they take."

Finding the 'best fit' for first-generation students

First-generation students may automatically look at public universities or private colleges with lower tuition rates as first choices for secondary education, but experts say not so fast.

"I would challenge your assumptions of where you think the cheapest place is going to be, because you might be surprised that a school like Princeton, for example, can often be cheaper for first-generation students than a non-Ivy school because they are very good at distributing grant money and providing financial aid," said O'Connell, the money expert. "It's a priority for them to make sure first-gen students are getting the opportunity that many other students are getting."

Penelope Campos, 20, found that to be the case as a first-generation college student. She is a rising junior at Cornell University, an Ivy League school in Ithaca, New York.

Campos grew up in the Bronx as the daughter of immigrants from the Dominican Republic. She didn't think of even applying to Cornell, where annual tuition ranges from $36,000 to nearly $55,000, until learning of the school's financial aid programs.

"I knew a few students who told me that Cornell has great financial aid, and it was definitely manageable, and I shouldn’t see it as an obstacle," Campos said of her decision to apply.

Even with her financial aid, Campos said she is still responsible for around $2,000 per semester in tuition plus her student activity fee and living expenses.

"Sometimes we have to pay tuition a little late and get fees," said Campos, who works part time on campus. "The financial aspect is still stressful because there are some [college] opportunities that I can't take advantage of or that I really have to think through because I just can't afford it."

Campos had the benefit of navigating the complex financial aid process with college counselors from New York Cares, the largest volunteer network in New York City that also runs college access programs.

"I didn't understand the financial aid packages at all. I didn't understand the terminology and my mom didn’t understand it at all and they helped explain it," she said. "Since I've been in college, I handle all the paperwork myself and just ask for my mom's signature when I need it. She may not understand the information I need or what they’re asking for."

Financial aid for first-gen students

First-generation students, in particular, should know that financial aid is available.

"There is so much money on the table, especially if you’re first-generation," said O'Connell. "Make a full-time job out of grant applications and scholarship applications."

The U.S. Department of Education alone awards more than $120 billion a year in grants, work-study funds and loans to more than 13 million students.

Private, nonprofit colleges and universities have a median endowment of $31.5 million, according to 2015-2016 data analyzed by the National Association for Independent Colleges and Universities (NAICU).

"The amount of financial aid that our colleges are providing students is significant,” said Pete Boyle, NAICU's vice president for public affairs. “They are trying so hard to get [first-generation and non-traditional] students on their campuses.”

At the University of Pennsylvania, another Ivy League school, the number of first-generation students attending has increased from 1 in 20, in 2005, to 1 in 8 students for the freshman class of 2017. In that same time, Penn's undergraduate financial aid budget increased by more than 180 percent, according to the university.

The school, whose president, Amy Gutmann, is a first-generation college student, offers a grant-based financial aid program for eligible students that does not include loans. Its undergraduate financial aid budget for fiscal year 2019 is $237 million.

Nearly 70 percent of grant aid awarded to students at four-year private colleges comes directly from institutional resources, compared to 25 percent at four-year public institutions, according to data analyzed by the NAICU.

"This is not completely altruistic," Tim Powers, NAICU's director of student aid policy, said of private colleges' financial aid programs. "First-generation students are valued contributors to our nation’s colleges and universities. They add a lot to the classroom discussion. They add a lot to the campus community. They help to broaden and inform debate, and colleges recognize the importance of bringing those voices and perspectives to their campuses.

He added, "Enrolling a first-generation student gives a college an opportunity to become a better place."